Hedge Fund Hurdle Rate (and High Water Marks)

A hedge fund’s hurdle rate is an important consideration when investing in hedge funds, especially since it has many variations. At the highest level, investors should understand what a hedge fund hurdle is, whether it is a hard hurdle, soft hurdle, or blended. Additionally, investors should evaluate whether the hedge fund hurdle rate is compounding or non-compounding as well as the existence and structuring of a high water mark mechanism.

Performance fees are also known as carry, carried interest, performance allocation, incentive allocations, or incentive fees (among other terms) and I’ll be using these term interchangeably. It is important to note that fees and hurdles can be assessed monthly, quarterly, annually, or longer. The below information and examples are just examples and investors are encouraged to carefully read the legal documents of any prospective investment.

Hedge Fund Hurdles

Hard Hurdle

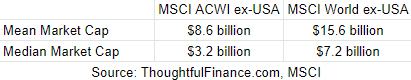

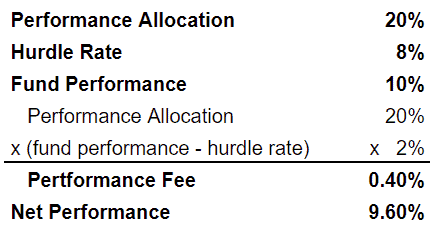

A hard hurdle means that the manager only collects a fee on the performance above the hurdle rate. This arrangement is more investor-friendly than a soft hurdle. Below is a detailed exampled of a hedge fund with a hard hurdle:

In the above example, the manager charges a 20% performance fee above an 8% hurdle. Since the fund returned 10%, the performance fee is .4% (20% multiplied by 2%).

Soft Hurdle

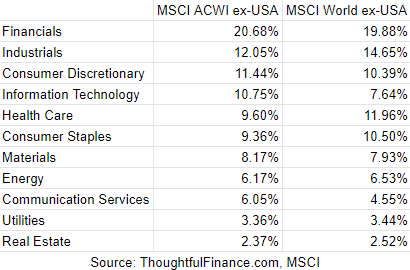

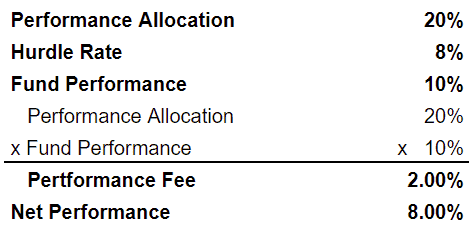

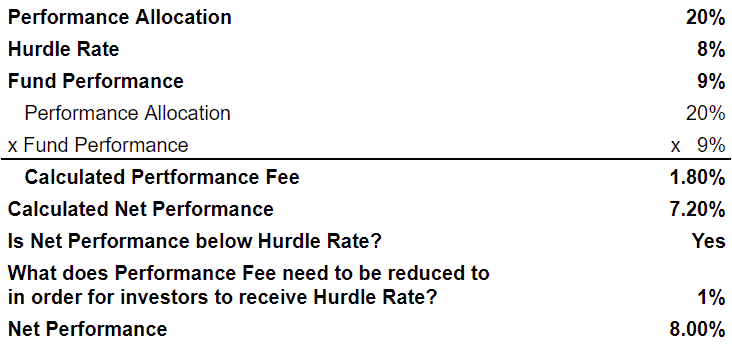

A soft hurdle means that the manager collects fees back to the first dollar of performance, assuming that gross performance exceeds the hurdle rate. This arrangement is more manager-friendly than a hard hurdle. Below is a detailed example of a hedge fund with a soft hurdle:

In the above example of a soft hurdle, the manager also charges a 20% performance fee above an 8% hurdle. However, the fee is applied on all returns (assuming fund performance exceeds the hurdle rate). So the performance fee is 2% (20% multiplied by 10%).

Blended Hurdle

A blended hurdle is similar to a soft hurdle in that a manager can collect fees back to the first dollar of performance (assuming that gross performance exceeds the hurdle rate). However, the performance fee is reduced if it would cause net returns to be lower than the hurdle rate. Below is a detailed example of a hedge fund with a blended hurdle.

Blended hurdles allow the manager to capture upside, while somewhat protecting investors.

Graduated Hurdle Rates

Similar to how a hedge fund with a blended hurdle allows a manager to have more upside than a hard hurdle, a graduated hurdle allows a manager to capture even more upside as performance increases.

Consider the following example of a hedge fund with a graduated hurdle. The performance fee may be 20% over an 8% hurdle, 30% over a 12% hurdle, and so on. Again, the hurdle can be structured to only apply to returns above the hurdle or to go back to the first dollar of returns. So an investor may pay a 20% performance fee up to 12% and a 30% performance fee on returns above 12%. Or they might pay 30% on all returns if the performance is above 12%.

Some investors believe graduated here fund hurdle rates improve the alignment of interests between managers and investors, while others believe that it incentivizes reckless risk taking.

Hedge Fund Hurdle Rate: Compounding vs Non-Compounding

Regardless of whether a fund has a hard hurdle or a soft hurdle, it is important to note whether the hedge fund hurdle rate is compounding or non-compounding. If it is non-compounding, investors should determine whether the performance fee is subject to a high water mark (see below).

Compounding

A compounding hurdle rate means that the hurdle rate compounds over time. Here is an example of a hedge fund with a compounding hurdle rate. If the hurdle rate is 6%, then the fund must return at least 12.36% over a 2 year period (since a 6% return compounded for 2 years is 12.36%). A hurdle rate could also be a benchmark index like the S&P 500 or a benchmark plus a spread (such as 3-month T-bills plus 200 basis points). Using these types of benchmarks could result in a negative hurdle rate, so the hurdle rate often has a floor of 0%.

Non-Compounding

If the hurdle rate is non-compounding, then it resets periodically. In other words, the hurdle rate will reset regardless of the prior periods performance. This is obviously manager-friendly (and unfavorable to investors).

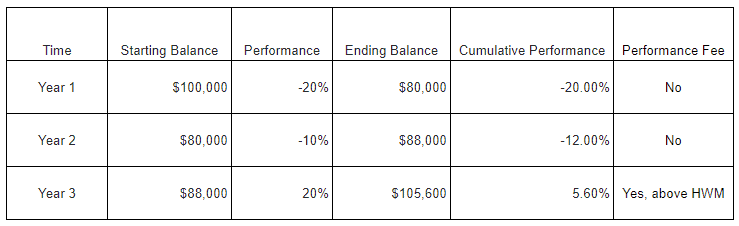

Consider this example of a hedge fund with a non-compounding 8% hurdle rate that loses 20% in Year 1 and gains 10% in Year 2. No performance fee would have been charged in Year 1, but it would have been charged in Year 2 (since the Year 2 performance exceeded the hurdle rate). Investors would be down 12% and yet still have to pay a performance fee! This example is detailed in the table below.

High Water Marks

A high water mark (or high-water mark or high watermark) is a tool frequently used to address the problems with non-compounding hurdle rates. A high water mark simply ensures that a performance fee cannot be charged until cumulative performance is positive.

Continuing from the previous example, below is an example of how a high water mark would prevent the manager from collecting performance fee in Year 2 (even though the hurdle rate is non-cumulative) because the cumulative performance is still negative. However, if the cumulative performance exceeded 0%, then the manager would be entitled to the performance fee.

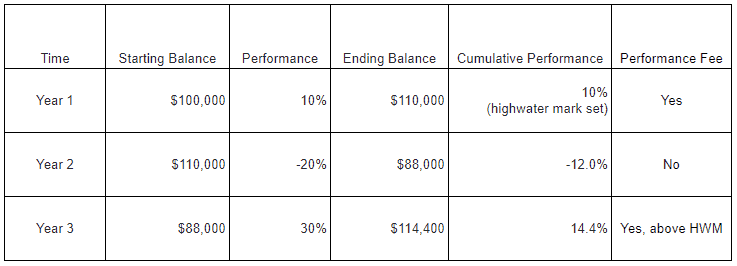

It is easy to think of other examples where a high water mark would protect investors. A common risk would be paying the performance fee twice on the same performance.

In the table below, we see an example of how a high water mark protects investors from paying fees on the same performance twice. Assume a fund returns 10% in Year 1 and -20% in Year 2 and then 30% in Year 3. The investment would have gone from 100,000 to 110,000 in Year 1 and again in Year 3 and investors would not want to pay for that twice. A high water mark ensures that they only pay a performance fee on the gains from 110,000 to 114,400 in Year 3.

Problems with High Water Marks

High water marks are a mechanism to protect investors. However, it can backfire in cases where managers severely underperform. If a fund is loses 50% from its high water mark, then the fund must return 100% to get back to even and qualify for performance fees again. Some managers may be de-motivated by this and decide to shut the fund down rather than continue without the near-term prospect of performance fees. Of course, if the manager launches a new fund, they can begin collecting performance fees immediately on any positive performance. There was a high profile example of this recently when the “meme stock” craze crushed Melvin Capital. First the hedge fund manager floated the idea of modifying the hurdle rate and high water mark, before ultimately deciding to shut down and reopen. This example highlights why hedge funds are infamous for playing a game where “heads I win, tails you lose.”

Conclusion

Ultimately, hedge fund hurdle rates, performance fees, and high water marks are designed to align the interests of managers and investors. The structure of these terms varies from fund to fund, depending on factors like manager size, asset class, and so on. There is no “best” set of terms, but investors should ask whether the terms create alignment in a variety of good and bad scenarios. This is also true when investing in real estate, private equity, and many other alternative investments beyond hedge funds.

Further Reading

The above primarily relates to hedge funds and vehicles structured similarly to hedge funds. However, a very similar set of concepts can be found in private equity preferred returns, catch-ups, and waterfalls.