An Updated Look at the Risks of Marketplace Lending

[This post originally appeared on LendAcademy, which is now FinTech Nexus News. Original can be found here: https://news.fintechnexus.com/an-updated-look-at-the-risks-of-marketplace-lending].

Several years ago, I wrote a two-part guest post about marketplace lending as an investment asset class. It has been truly amazing to watch the industry’s growth and see how widely marketplace lending is now accepted as a bona fide asset class. The industry’s maturation has mitigated many risks, but I also believe that the rapid growth and increasing competition has increased other risks.

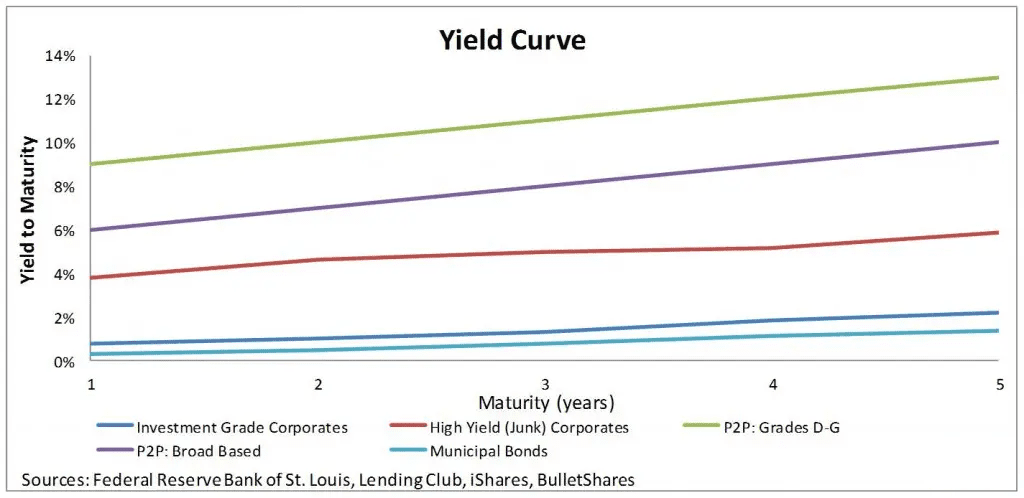

The primary risks today, in my opinion, stem from the decline in lending rates. Although rates were declining in 2013 (when I first invested in and wrote about marketplace loans), rates were much higher then. Today, rates have already come down significantly and continue to decline. Lower projected returns translate to a narrower margin of safety. Many, if not all, of the below risks have existed for quite some time and have been widely expected at some point, but they warrant more caution now due to today’s lower and still-declining rates.

Loan Refinancing

One factor that has been driving down returns has been loan refinancings, which represent a conflict of interest between investors and the platforms. Investors would generally prefer to hold performing loans to maturity in order to maximize returns, whereas the platforms are incentivized to originate as many loans as possible in order to maximize revenue. These are not mutually exclusive interests, but the platforms have been actively soliciting existing borrowers to refinance their loans at lower rates for the past several years. This is not inherently wrong (it’s great for borrowers), but investors should realize that a conflict of interest exists and that their loans are callable at any time (which is detrimental during a period of declining rates, since reinvestment returns will be lower). Orchard Platform recently posted a good summary of this issue here.

Loan Quality Questions

As more platforms go public, the pressure to grow continues to increase. Growing loan volume needs to be carefully weighed against maintaining loan quality. My observation is that both the pressure to grow and the huge demand for loans has led to a loosening of underwriting standards. We are seeing explicit examples, such as “high yield” offerings and euphemistically named “near prime” loans. But several sources have also confirmed that at least some platforms are now accepting less borrower documentation than they have in the past. My hope is that the technology used in place of traditional underwriting methods is robust enough to make up for the weaker verification processes. Only time will tell.

Questionable Practices in the Corners of Business Lending

The 2015 LendIt conference in New York (highly recommended!) was a great showcase of the industry and I met a ton of interesting people and learned about many marketplace lending platforms that focus on business lending. However, a few of the business lending platforms and funds were extremely aggressive. I am not trying to be moralistic, but it was honesty difficult to tell whether some of the platforms were helping or exploiting borrowers. A more economic concern is that several claimed that their high-degree of collateralization mitigated a lot of risk, but further questioning about recovery rates called many of these claims into question. This certainly does not apply to the entire business lending segment, but I would encourage investors to research any platform and/or manager that they are considering.

Investor Risk Analysis

The platforms’ risk models appear much more robust, but my guess is that many individual investors rely on some of the public commentary that compares the credit risks of marketplace lending with the credit risks of credit cards. This is an imperfect analog, at best, since revolving consumer credit (like credit cards) is fundamentally different from non-revolving personal loans (like marketplace lending) on many levels. For instance, a troubled credit card customer has an incentive to continue paying their monthly bill so that they can continue to use the card. A marketplace lending borrower does not have that incentive. This is not a prediction that marketplace loan loss rates will exceed credit card loss rates in the next economic downturn (although they may), but I would encourage investors to consider possible losses carefully.

Conclusion

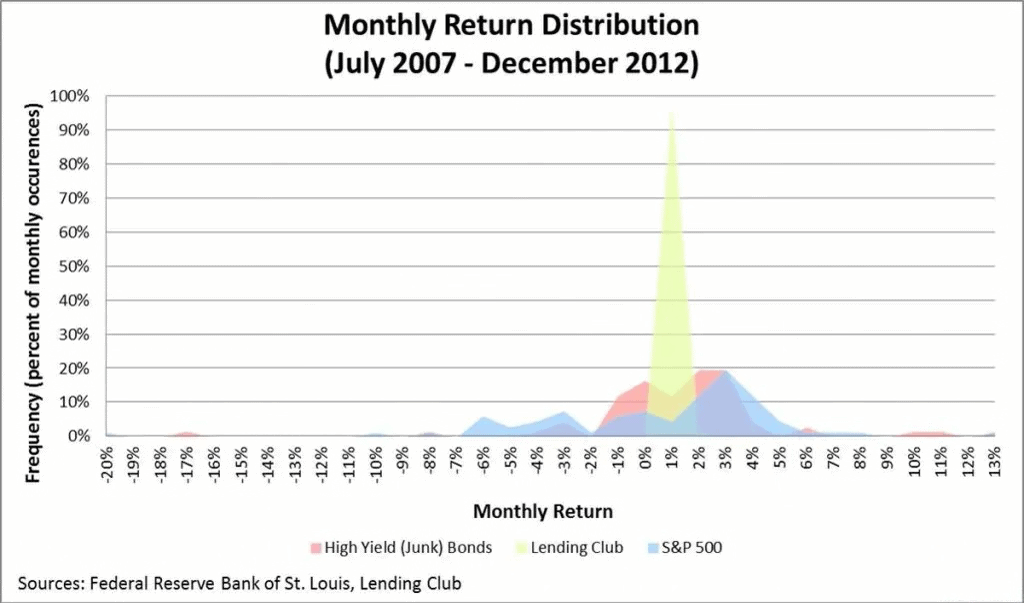

As “peer-to-peer lending” matures towards “marketplace lending,” the high returns of early-adopters are now trending down towards market-driven ones. I believe marketplace lending will provide positive returns for quite some time, but the margin of safety is narrowing and its relative value to other investable markets has diminished as well. My hope is that all parties protect the integrity of the asset class, to ensure its long-term viability. Of course, hope is not a prudent investment strategy, which is why I am writing this and encourage all marketplace lending investors to recognize and weigh the risks along with the opportunity.

Full Disclosure: I advise clients on private investment vehicles dedicated to the marketplace lending asset class, as well as personally own loans on both the Lending Club and Prosper platform. I am also a client of NSR Invest.