An important consideration when investing in private equity is the preferred return, which is not a standardized term and has many variations. At the highest level, private equity investors should understand what the preferred return is as well as how its calculated, what the catch-up is (if any) and whether there are claw back provisions. Additionally, investors should evaluate whether the preferred return is simple, compounded, cumulative, and so on.

Performance fees are also known as carry, carried interest, performance allocations, incentive allocations, or incentive fees (among other terms) and I’ll be using them interchangeably. Private equity funds are typically long-term closed-end vehicles, so the below information and examples are more conceptual than anything else. They are examples of private equity preferred returns and investors are encouraged to carefully read the legal documents of any prospective investment.

Preferred Returns: Pure vs Catch-Ups

Pure Preferred Return

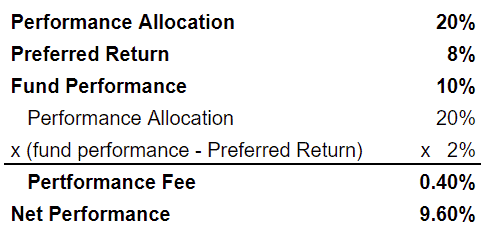

Pure preferred return is also known as a “true preferred return” or a “hard preferred return” (similar to a “hard hurdle” in hedge fund lingo, although use the term in a private equity context too). A pure preferred return means that the manager only collects a fee on the performance above the preferred return. This arrangement is more investor-friendly than the alternative of a “preferred return with catch-up.” Below is a detailed example of a private equity pure preferred return:

In the above example, the manager charges a 20% performance fee above an 8% preferred return. Since the fund returned 10%, the performance fee is .4% (20% multiplied by 2%).

Preferred Return with Catch-Up

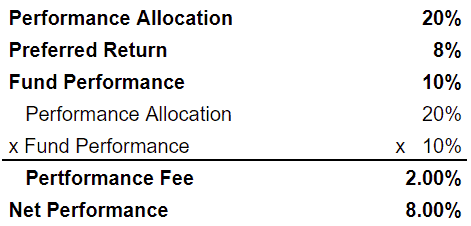

A preferred return with catch-up means that the manager collects fees back to the first dollar of performance (the manager “catches up”), assuming that gross performance exceeds the preferred return. This arrangement is more manager-friendly than a pure preferred return. Below is a detailed example of a private equity preferred return with catch up:

In the above example with catch-up, the manager also charges a 20% performance fee above an 8% preferred return. However, the fee is applied on all returns (assuming fund performance exceeds the preferred return). So the performance fee is 2% (20% multiplied by 10%).

100% Catch-up

Once performance hits 7%, all additional returns accrue to the manager until gross performance surpasses 8.24% (because 7% is 85% of 8.24%). In other words, investors receive the returns from 0% to 7% and the manager receives returns from 7% to 8.24%. Returns of 8.25% and beyond are split 85%/15% between the investors and manager.

50/50 Catch-up

A 50/50 catch-up is a common catch-up structure, although it could be 60/40, 75/25, or any other combination.

Let’s look at an example of a private equity preferred return with a 50/50 catch-up. A private equity fund fund has 20% performance fee above a 10% preferred return with a 50/50 catch-up provision. In this case, the investors would receive all of the returns up to 10%. Additional returns would be split 50/50 until gross returns hit 12.5%. At 12.5%, the manager would be fully caught-up since they would receive 50% of the returns from 10% to 12.5% or 1.25% (which is 10% of 12.5%). Returns above 12.5% would be split 90/10 between the investors and manager.

Catch-Up Modifications and Limitations

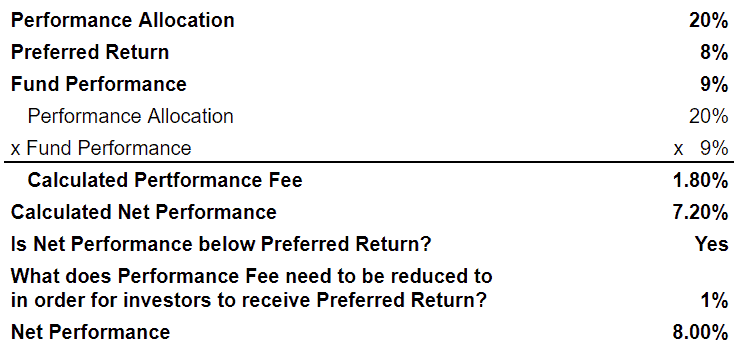

Some funds have a structure where the manager earns carried interest back to the first dollar of performance (assuming that gross performance exceeds the preferred return), but the performance fee is reduced if it would cause net returns to be lower than the preferred return. Below is a detailed example of this modified structure private equity waterfall structure.

This structure allows managers to retain the upside, while somewhat protecting investors.

Tiered Preferred Returns

Similar to how a catch-up allows managers to have more upside than a pure performance return, a tiered preferred return allows managers to capture even more upside as performance increases.

Here’s an example of a private equity fund with tiered performance fees. The performance fee may be 20% over an 8% preferred return, 30% over a 12% preferred return, and so on. The performance fee can be structured to only apply to returns above the preferred return or to go back to the first dollar of returns. So an investor may pay a 20% performance fee up to 12% and a 30% performance fee on returns above 12%. Or they might pay 30% on all returns if the performance is above 12%. The fees at different tiers can also be limited so as to not push returns below the tier that they are being charged fees for.

Some investors believe that tiered preferred returns in private equity improve the alignment of interests between managers and investors, while others believe that it incentivizes risky behavior.

Simple, Compounding, and Resetting

Regardless of whether a private equity fund has a pure preferred return or a catch-up, it is important to note how the preferred return rate is quoted and how it works.

Simple Preferred Returns

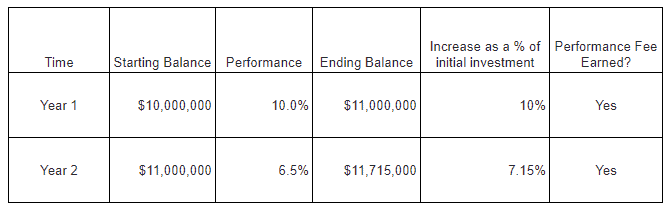

Some private equity preferred returns are quoted as a simple rate, which is generally not a great arrangement for investors. Consider the example in the below table where a fund may have a preferred return of a 7%. In this case, the fund will be entitled to its performance fee as long as it returns at least 7% on invested capital. So if the fund starts with $10 million and returns are 10% in Year 1, the manager gets the performance fee. However, if the fund returns 6.5% in Year 2, the manager still gets the performance fee. This is because the $715,000 (calculated as 6.5% x $11 million) that it earned in Year 2 is more than 7% of invested capital (of $10 million).

This model is obviously favorable to managers, although it may make sense for certain open-ended vehicles (and may not matter for some closed-end vehicles).

Compounded Preferred Returns

Some private equity preferred returns are quoted as an annually compounded rate. If the preferred return is 6%, then the fund must return at least 12.36% over a 2-year period (since a 6% return compounded for 2 years is 12.36%), 19.1% over a 3-year period (since a 6% return compounded for 3 years is 19.1%), and so on.

Non-cumulative Preferred Returns

The advent of evergreen and open-ended private equity has resulted in some preferred returns that are “non-cumulative” and reset periodically. In other words, the preferred return will reset regardless of the prior periods performance.

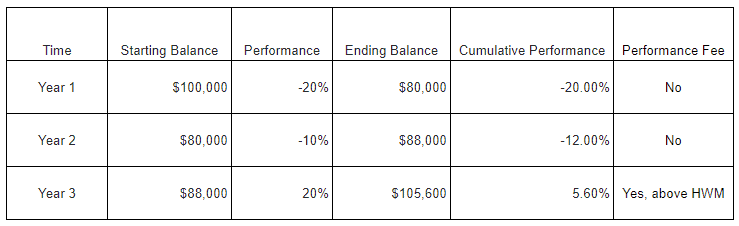

This is obviously manager-friendly (and unfavorable to investors). Consider a fund with an 8% preferred return that that loses 20% in Year 1 and gains 10% in Year 2. No performance fee would have been charged in Year 1, but it would have been charged in Year 2 (since the Year 2 performance exceeded the preferred the return). Investors would be down 12% and yet still have to pay a performance fee! This example is detailed in the table below.

High Water Marks

A high water mark (or high-water mark or high watermark) has primarily been used by hedge funds historically, but it is becoming more common in private equity due to the wave of evergreen offerings with non-cumulative performance fees.

A high water mark is a mechanism to address the downsides of a non-cumulative preferred return. Furthermore, it ensures that a performance fee will not be charged until cumulative performance is positive. Returning to the previous example, a high water mark would prevent the manager from collecting performance fee in Year 2 (even though the preferred return resets in the new year) because the cumulative performance is still negative. However, once the cumulative performance exceeds the 0%, then the manager would be entitled to the performance fee.

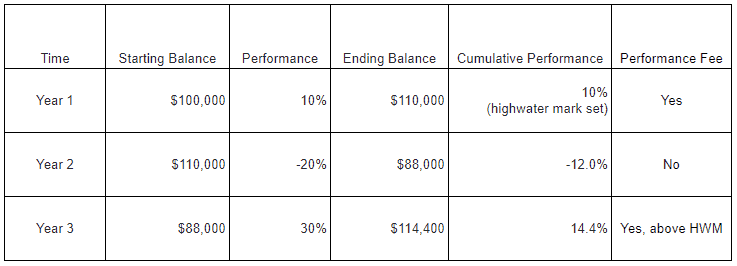

It is easy to think of other examples where a high water mark would protect investors. A common risk would be paying the performance fee twice on the same performance. In the chart below, we assume a fund returns 10% in Year 1 and -20% in Year 2 and then 30% in Year 3. The investment would have gone from 100,000 to 110,000 in Year 1 and again in Year 3 and investors would not want to pay for that twice. A high water mark ensures that they only pay a performance fee on the gains from 110,000 to 114,400 in Year 3.

Private Equity Waterfall Structures

I’ll probably write another post on this, but there are two main types of “waterfalls” or ordering of distributions.

European Waterfall

Under a European waterfall structure, investors typically receive their return of capital and preferred return before the manager begins receiving its fee carried interest catch-up. Given that many private equity funds are 10 year funds (plus extensions), managers may be waiting a very long time before receiving any carry from the waterfall.

American Waterfall

Under an American waterfall, the manager is allowed to receive advances of its carried interest catch-up on a “deal-by-deal” basis. Essentially, this allows the manager to receive some compensation earlier. Proponents of this structure argue that it allows managers to think longer-term and not sell assets prematurely in order to generate income for themselves.

Clawback Provisions

Clawback provisions are important for investors to have under an American waterfall structure. It provides a mechanism for investors to receive some compensation from the manager if the deal-by-deal carried interest fees that are advanced are ultimately more than what the manager is entitled to (once the fund is fully wound down and the actual fees known). Unfortunately for investors, clawbacks are generally net of taxes since managers argue that they cannot refund what they paid to the IRS. So investors may receive a fraction of what was overpaid to the manager.

Conclusion

Ultimately, performance fees, preferred returns, and high water marks are designed to align the interests of private equity managers and investors. The structure of these terms varies from fund to fund, depending on factors like manager size, asset class, and so on. There is no “best” set of terms, but investors should ask whether the terms create alignment in a variety of good and bad scenarios. This is also true when investing in real estate, hedge funds, and many other alternative investments beyond private equity.

Further Reading

The above primarily relates to private equity and vehicles with a “private equity structure”. However, a very similar set of concepts can be found in hedge fund hurdles, hurdle rates, and high water marks.