Vanguard Mutual Fund & ETF Share Class Structure

Vanguard is one of the largest asset managers in the world and their funds use a unique share class structure that includes ETFs. Vanguard ETFs are essentially a share class of their mutual funds. This patented structure generates tax benefits for Vanguard mutual fund owners. Like many mutual fund complexes, Vanguard offers a variety of institutional and retail share classes. Individual investors generally have access to the following Vanguard share classes:

- Investor Shares

- Admiral Shares

- ETFs

Readers interested in current funds available, minimums, etc., should check out Vanguard’s share class page and read below for a general overview of how Vanguard’s share classes work.

Vanguard Mutual Fund Share Classes: Admiral Shares vs Investor Shares

Investor Shares

Many of the mutual funds that Vanguard initially offered to individual investors were from the Investor share class, or “Investor Shares.”

Over time, Vanguard has phased many index fund Investor Shares, although Investor Shares remain open for many of their non-index actively-managed funds. In some cases, the funds closed to new investors (but remain open to existing investors wishing to increase allocations). In other cases, the funds were merged with other funds or consolidated into the Admiral share class.

There are different business reasons for each phase out, but investors are not necessarily missing out. The Investor Shares are generally the most expensive share class of each Vanguard fund.

Admiral Shares

The Admiral share class was launched back in 2000. Originally, these “Admiral Shares” had higher investment minimums and lower expenses than the Investor Shares. However, the Admiral Shares are now the only mutual fund share class available to many investors. Fortunately, the minimum investment for many Admiral Shares is down to $3,000.

Vanguard’s ETF (share class)

Vanguard began launching ETFs in 2001. Interestingly and importantly, is the Vanguard ETF share class structure; many Vanguard ETFs are structured as a share class of their mutual funds. Just as Investor Shares shares and Admiral Shares shares are different share classes of single funds, ETFs are also a share class of the same fund. Vanguard patented this innovation, although that patent expires in May 2023.

ETF Tax-Efficiency

ETFs are generally more tax-efficient than mutual funds due to ETFs’ ability to make “in-kind” redemptions. That is, the fund pays the redeeming investor in stock or bonds rather than cash.

When an investor redeems shares of a mutual fund, the fund must sell assets to raise cash to pay the investor. These sales often realize capital gains and funds are obligated to make a taxable distribution based on any net capital gains.

When shares of an ETF are redeemed, the fund can distribute fund assets in-kind (rather than selling to raise cash). Since no sales are made, no capital gains are realized. If no capital gains are realized, then no taxable distributions will be made. (Note: ETFs are typically traded between investors on an exchange. However, some shares are also created and redeemed by Authorized Participants [APs]).

Tax-Efficiency of Vanguard Mutual Funds

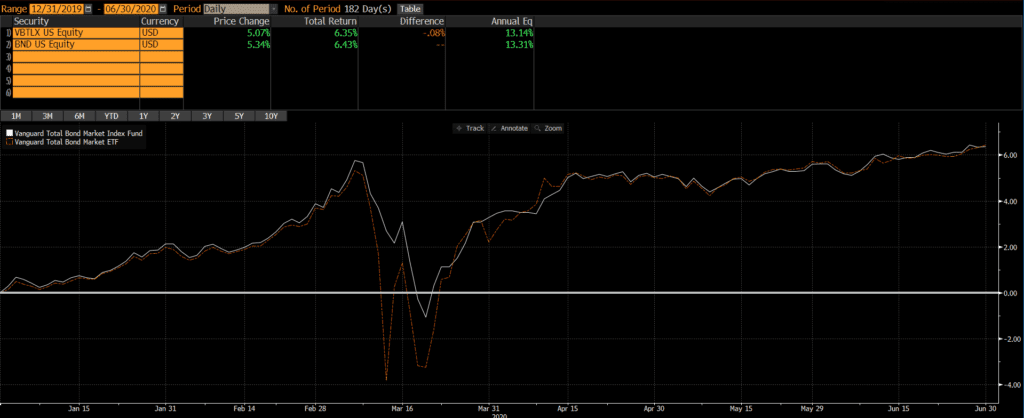

ETFs are able to avoid realizing a lot of capital gains by making in-kind distributions from the pool of assets that they represent. In the cases where a Vanguard ETF is one of several share classes, then the ETF and the other mutual fund share classes represent the same pool of assets. This means that a Vanguard ETF’s in-kind distributions benefit both itself and its related share classes. Thus, Vanguard mutual funds are generally just as tax-efficient as ETFs.

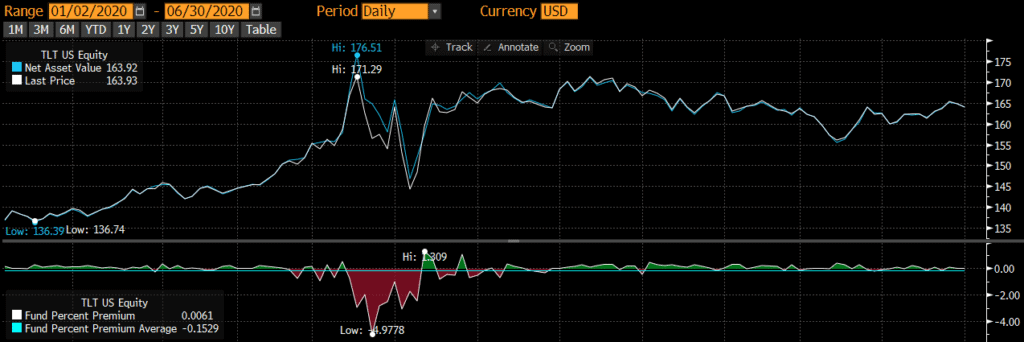

Bond ETF Risks

ETFs are generally more tax-efficient than similar mutual funds, but that is not necessarily the case with Vanguard. So the decision to use an ETF versus an Admiral Share is often a close call and may not make any difference at all.

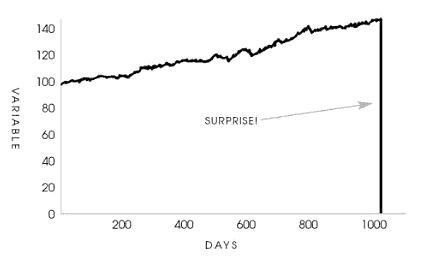

The one asset class where I almost always use mutual funds rather than ETFs is fixed-income. I’ve written extensively about the risks of bond indices and bond ETFs, but the tl;dr version is that indexing is not quite a beneficial for fixed-income (relative to equities), the major bond indices have problems, and ETFs are not a well-suited for fixed-income. There are some exceptions, but I generally steer clear of fixed-income ETFs.

Vanguard Share Class Conversions

Investor Share Class to Admiral Share Class Conversion

Vanguard’s share class conversion program allows holders of Investor Shares to convert their holdings to Admiral Shares. The conversion only works in one direction, so Admiral share class owners cannot convert their shares into Investor Shares. A tutorial on how to make this conversion is on Vanguard’s website.

Vanguard Mutual Fund to ETF Conversion

Vanguard’s share class conversion program also allows investors in some of its mutual funds to convert their shares from the mutual fund share classes to the ETF share class. This conversion only works in one direction, so ETF holders cannot convert from ETFs to a mutual fund share class. A full list of funds eligible for share class conversion can be found on Vanguard’s site.

Implications for Investors

The answer to the question of whether to use Vanguard Admiral Shares vs Investor Shares is: it depends.

The decision to use Investor Shares, Admiral Shares, or ETFs depends on investor-specific factors, such as custodian/brokerage, portfolio and allocation size, transaction costs, tax profile, liquidity needs, and so on. Investors should evaluate these factors in the context of their own situation.