Hard money loans are an attractive asset class in many different environments. That being said, the characteristics of hard money loans make hard money investing especially attractive in low rate and/or rising rate environments. Below are some factors to consider before investing in hard money loans in different rate environments.

Readers unfamiliar with hard money loans as as asset class can read our post about investing in hard money loans.

Investing in Hard Money When Rates Are Low

I first became acquainted with hard money investing in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when yields dropped precipitously. The public markets did not offer the yields that they once did, so I was forced to find ways to generate income without being exposed to excessive interest rate risk. Below are several reasons that hard money loans are an especially attractive asset class when rates are low.

Above Market Returns

The primary reason that hard money loans are attractive is because the expected returns are often higher than what can be found in publicly-traded assets. This is the case nearly all of the time, but the spread between hard money and traditional bonds is often widest when in low rate environments.

Points

Hard money lenders typically charge points on the front-end and/or backend of loans. So borrowers may pay 1% of the loan value upfront and another 1% at final payoff. Again, this is true throughout time, but points represents even more relative returns when rates are low (and some bonds may only pay 1-2% per year)!

Rates

Hard money rates are typically in the 5-20% range depending on a variety of factors. Even at the low end of this range, 5% is much higher than what many public fixed-income investments yielded from 2008 to 2022.

The after-tax spread is narrower for taxable investors, although the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 TCJA helped hard money investors a little bit. In the wake of the TCJA, many hard money debt funds elected to be treated as REITS or created sub-REITS (where the fund would own a single REIT which would own the underlying loans). In either case, investors are able to avoid paying tax on 20% of their REIT-related income.

Of course, those who invest in hard money through tax-deferred accounts (such as IRAs, 401k’s, etc) or tax-exempt accounts (such as Roth IRAs and so forth) don’t have to worry about the tax inefficiency of hard money investment returns.

Penalties

Hard money loans typically have penalties and charge a penalty interest rate in the case of default. Furthermore, lenders are often able to actually collect these fees in the case of default because hard money loans are typically secured loans and include recourse. I’m no fan of a “loan to own” approach, but defaults often result in higher returns for hard money investors.

Contrast this to corporate bonds, which are often unsecured. Defaults nearly always result in lower returns for investors rather than higher returns. The possibility of defaults (by hard money borrowers or corporate borrowers) may be higher during periods of low rates as low rates can be a sign of economic weakness (either episodic or prolonged).

Low Duration

Hard money loans are short-duration assets, which is important when rates are low. The term low rates implies that rates could be higher and anyone investing in a low rate environment should be aware of the possibility and risks of rising rates. Fortunately, I believe hard money is also attractive in a rising rate environment.

Investing In Hard Money Money When Rates Are Rising

Hard money loans are an attractive asset class in many types of environments, including periods of rising interest rates. This is largely due to their short duration and illiquidity, although extension costs and floating rates can also benefit investors.

How Do Hard Money Loans Perform When Rates Rise?

People often ask me what happens to hard money rates when Treasury rates increase (or decrease). My answer is always: it depends. It depends on the level of risk aversion in the marketplace. Below are two real examples from the past few years:

Consider the Federal Reserve’s hiking cycle of 2018. The Fed increased rates quite a bit and yet hard money rates declined. This is because risk appetite was high (and risk aversion was low) leading to more competition to lend and lower rates.

Contrast this with the Fed’s hiking cycle of 2022. Not only did the risk free rate increase quite a bit due to the Fed, but risk aversion increased across the board and lenders pulled back (or exited the market altogether). Thus, competition for loans declined and rates increased quite a bit.

Risk Free Rate vs Spread

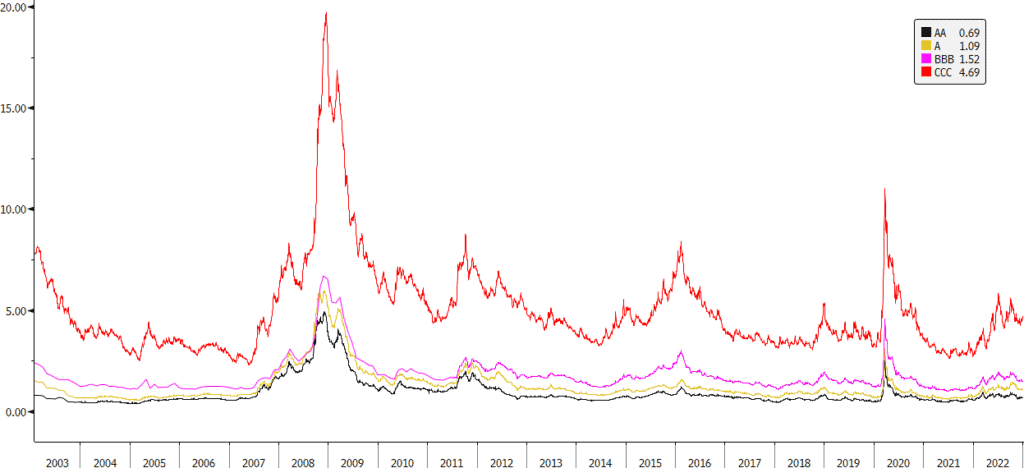

The above examples illustrate the fact that rates in the marketplace consist of two components: the “risk free rate” which refers to Treasury rates and a spread above that (to compensate for the risk of lending to a non-government borrower).

To illustrate this, consider when Treasury rates fell dramatically in February and March of 2020. Rates for non-government borrowers did not fall dramatically. Rather, rates skyrocketed because there was so much fear, uncertainty, and risk that the increase in spreads more than offset the decline in the risk free rate. In other words, the rates that non-government borrowers pay is more correlated to spreads than the risk free government rate.

Short Duration

Many hard money loans are have maturities from six months to three years. So the loans are turning over relatively quickly. In a period of rising rates, short duration assets tend to perform better because income can be reinvested into higher rates more quickly. Thus, in general, hard money loans tend to perform well when rates are increasing because the interest and payoffs are reinvested at higher rates more quickly.

Extensions

Many hard money loans contain the option to extend a loan. That is, a borrower can extend a loan beyond its original maturity date for a predetermined about of time, perhaps 3, 6, or more months. However, exercising an extension option often comes along with an increase in the interest rate.

In some rising rate environments, borrowers may find it more difficult to payoff a hard money loan either because it is more difficult to sell real estate or more difficult to refinance real estate. In these situations, extensions may be exercised more often.

Floating Rates

Some hard money loans are variable rate. Rather than paying a fixed interest rate, borrowers pay a floating rate that consists of a reference rate and a spread. For instance, instead of specifying a flat 9%, the loan may specify that the rate is SOFR plus 4%. If SOFR is 4.5%, then the rate is 8.5%. If SOFR goes up to 5%, then the loan rate increases to 9%. Previously many loans were tied to LIBOR, but SOFR has largely replaced LIBOR in the US. The reference rate could also be the Fed Funds rate, “Prime,” various Treasury rates, or swap rates.

Some floating rates may have an interest rate floor well below current rates. Using the above example of SOFR plus 4%, the loan might have a floor of 6%. So even if SOFR goes below 2%, the lowest possible interest rate would still be 6%. Other lenders will set the floor at the current rate levels, so the floor would be 8.5% if SOFR is 4.5% and there is a 4% spread.

Illiquidity

Most hard money loans are held on private balance sheets rather than securitized into the bond market. Many fixed-income investments decline in value when rates rise. However, hard money loans are typically held at par rather than marked to market, so investor redemptions are typically paid out at par. Therefore, hard money loans often offer more principal protection against rising rates than publicly-traded fixed-income.

Credit Quality

Rising rates can create problems for borrowers, so credit quality is especially important in rising rate environments. For instance, if real estate values decline, hard money lenders better make sure that their loan-to-value (LTV) ratios are conservative enough. Similarly, rising rates may mean that borrowing costs increase as a percentage of revenue and that borrowers may have more difficult refinancing a hard money loan with permanent financing (since the future debt service coverage [DSCR] ratio may not be sufficient). In other words, lenders must take extra care to ensure credit quality standards; otherwise losses would offset all of the benefits listed above.

Allocating to Hard Money During Rising Rates

In a rising rate environment, investors are generally better off allocating to floating rate loans. In an environment with declining rates, allocating to fixed rates may make more sense. Of course, it depends on what the current yield of the portfolio is, the proportion of fixed-rate and floating-rate loans, what the reference rate refers to, as well as where the various rate floors are at. First and foremost though, investors should always focus on credit quality as return of capital is always more important than return on capital.

Investing in Hard Money When Rates are High

It can still make sense to invest in hard money when rates are high, but it is perhaps not as attractive as when rates are low. The spread between hard money and traditional fixed-income is compressed, so there is much less opportunity cost than investing bonds. Additionally, investors may prefer to have more duration in order to benefit from appreciation if rates decline (since bond prices generally move inversely to rates).

In high rate environments, investors should continually ask themselves how much additional yield (or after-tax yield) do they need to compensate for the risk and illiquidity of hard money loans. At some point, it is more attractive to invest in public fixed-income rather than hard money loans. Again, that may be a higher bar for tax-advantaged accounts/investors who do not have to worry about the after-tax yields of such a tax-inefficient asset class.

Investing in Hard Money When Rates are Falling

There are pros and cons to being invested in hard money when rates are falling. One the one hand, hard money investors should continue to receive higher interest rates for a few months or years, as the existing loan book doesn’t refinance or payoff overnight. On the other hand, as an illiquid investment held on small private balance sheets, hard money loans do not generally benefit from declining rates in the same ways that publicly-traded bonds do through rising values.

Also, investors should evaluate why rates are falling. If rates are declining due to economic weakness, then credit quality is of utmost importance as borrowers and real estate may face difficulties.